Although I can recall having heard about similar stories in the past, a recent news story caught my eye in which a Lakewood, New Jersey couple had been sentenced in a plot to extort a divorce. They, along with others, were accused of involvement in a scheme involving the kidnap and/or assault of husbands in an effort to force them to agree to give their wives a Jewish divorce, or Get. Although in our practice, we deal with “civil” as opposed to “religious” divorces, the inter-relationship of the two occasionally comes up. The subject of this blog post is to briefly address how the family courts of this State have dealt with these sorts of issues, and some practical considerations of how to deal with them so as to avoid the extreme situation noted above.

Without delving into a religious discussion, these sorts of issues arise due to the distinction between a “civil” marriage and a “religious” marriage, and the religious consequences involved in dissolving such marriages. Many people are married in purely “civil” ceremonies. They are married by a Judge, Mayor or other official legally authorized to officiate a ceremony of marriage. Many still participate in a religious ceremony of marriage officiated by a Priest, Rabbi, Pastor or other religious authority empowered to do so within their religion. Such religious ceremonies are considered legally recognized “civil” marriages as well. While all may be married within the eyes of the law, in many religions, the couple is considered married in the eyes of God as well. It is this distinction which is at the root of the complications for some when that marriage dissolves.

When the courts of this state grant a divorce dissolving a marriage, they are doing so as a “civil” divorce. The couple is divorced in the eyes of  the law. However, for some religions, a “civil” divorce has no impact upon that couples’ marriage bond in the eyes of God. For most Christian denominations marriage is recognized as a lifelong covenant. This is particularly so in the Roman Catholic and other orthodox denominations for when couples participate in a sacramental marriage ceremony. A “civil” divorce is not recognized as having broken that sacramental marriage bond. Therefore, a person would not be allowed to remarry in the church as long as their former spouse was alive unless that marriage was religiously annulled by the church. Similarly, while under Judaism, divorce is recognized and accepted, for a Jewish divorce to be effective, the husband must hand to the wife a bill of divorcement known as a Get which acts as proof of their divorce and which would enable the wife to remarry in the Jewish faith. The failure of the husband to deliver a Get to the wife would not only impact the wife’s ability to remarry, but would also have profound consequences as to the religious status of any future children that she may bear. A Get cannot be granted by a court as part of a “civil” divorce, but can only be awarded by a proceeding before a Bet Din, a Jewish ecclesiastical forum. These sorts of issues usually arise for those who practice in the conservative or orthodox Jewish communities. Divorce is generally allowed and recognized in Islam and most Eastern religions, although each has their own unique terms and conditions as well.

the law. However, for some religions, a “civil” divorce has no impact upon that couples’ marriage bond in the eyes of God. For most Christian denominations marriage is recognized as a lifelong covenant. This is particularly so in the Roman Catholic and other orthodox denominations for when couples participate in a sacramental marriage ceremony. A “civil” divorce is not recognized as having broken that sacramental marriage bond. Therefore, a person would not be allowed to remarry in the church as long as their former spouse was alive unless that marriage was religiously annulled by the church. Similarly, while under Judaism, divorce is recognized and accepted, for a Jewish divorce to be effective, the husband must hand to the wife a bill of divorcement known as a Get which acts as proof of their divorce and which would enable the wife to remarry in the Jewish faith. The failure of the husband to deliver a Get to the wife would not only impact the wife’s ability to remarry, but would also have profound consequences as to the religious status of any future children that she may bear. A Get cannot be granted by a court as part of a “civil” divorce, but can only be awarded by a proceeding before a Bet Din, a Jewish ecclesiastical forum. These sorts of issues usually arise for those who practice in the conservative or orthodox Jewish communities. Divorce is generally allowed and recognized in Islam and most Eastern religions, although each has their own unique terms and conditions as well.

With that as a primer, to what extent have these sorts of issues been dealt with by the family courts of this State? The first question, however, is how or why are “civil” courts finding themselves entangled in such religious controversies? Virtually all of the cases in New Jersey which have considered these issues involved, in one form or another, a husband’s refusal to secure or deliver a Jewish Get to his wife.

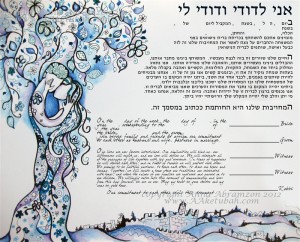

In the case of Minkin v. Minkin, 180 NJ Super 260 (Ch. Div. 1981), the wife moved post-judgment for an Order requiring the husband to obtain and pay the cost of a Get. The parties had been married in a Jewish ceremony where they entered into a contract called a Ketubah in which they agreed to conform with the provisions of the laws of Moses and Israel, including a requirement that the husband give the wife a Get. The husband alleged an act of adultery on the wife’s part. He refused to obtain a Get and he opposed the wife’s motion, claiming that it would violate the Establishment of Religion Clause of the First Amendment. First, the Court determined that the parties’ marriage contract (Ketubah) was not against public policy but merely required the participants to comply with certain reciprocal obligations pertaining to the marriage. As to the husband’s First Amendment arguments, the Court referred to the three prong test under the United States Supreme Court case of Committee for Public Education & Religious Liberty v. Nyquist, 413 U.S. 756 (1973), namely that the law in question (1) must reflect a clearly secular legislative purpose; (2) must have a primary effect that neither advances nor inhibits religion and (3) must avoid excessive entanglement with religion. After considering the testimony of several Rabbis, the court concluded that the acquisition of a Get was not a religious act, that compelling the husband to secure a Get would have a clear secular purpose of completing a dissolution of the marriage, neither advanced nor inhibited religion since it did not require the husband to participate in a religious ceremony or do acts contrary to his religious beliefs nor would it involve an excessive entanglement with religion, and that the Get was a release document devoid of religious connotation, noting that the law authorizes clergy to perform marriages and permits use of a religious ceremony to do so. Therefore the court determined that it could order the husband to specifically perform his obligations under the Ketubah and secure a Get.

A similar situation confronted the court in Burns v. Burns, 223 NJ Super 219 (Ch. Div. 1988). The parties divorced and the wife wanted to remarry but could not do so under Jewish law without obtaining a Get. The husband refused unless the wife agreed to invest $25,000 into an irrevocable trust for the benefit of their daughter. The court noted that the husband’s offer to secure a Get for $25,000 made this a question of money, not religious belief. Further, the court found that circumstances under the Law of Moses and Israel when the husband would be required to secure a Get under a Ketubah were broader than just in cases of adultery. Adopting the principles enunciated in Minkin, the court found that compelling the husband to submit to the jurisdiction of the Jewish ecclesiastical court, the Bet Din, and initiate the procedure to secure a Get was within the equitable powers of the court to do, noting that the ultimate decision of whether a Get was granted was that of the Bet Din and not the court.

While not involving an order to compel someone to secure a Get, in the case of Segal v. Segal, 278 NJ Super 218 (App. Div. 1994), the wife contended that the parties’ marital settlement agreement, in which the husband had refused to give the wife a Get unless she waived virtually all financial claims in the divorce, was a produce of duress. In reversing the decision of the trial court, the Appellate Division concurred that same had been the product of overreaching and duress, citing to the Burns decision as well as various New York cases which had considered the issue.

However, in the case of Aflalo v. Aflalo, 295 NJ Super 527 (Ch. Div. 1996), the court disagreed with the course followed in the Minkin and Burns cases, and declined to order the husband to secure a Get. In this pre-judgment matter, the husband refused to go along with the wife’s request that he cooperate in securing a Get; he had actually taken action with the Bet Din to have a hearing on his attempts at reconciliation. The court offered its own over view of First Amendment jurisprudence in regards to the Free Exercise of Religion Clause, the principles surrounding a Get under Jewish law, and its criticism of the reasoning of the courts in Minkin and Burns. Among other things, the court believed that the Free Exercise rather than the Establishment Clause prohibited a government from interfering or becoming entangled in the practice of religion, and that a court cannot decide questions of religious doctrine which it believes this was, notwithstanding the conclusions of the court in Minkin. The court was of the view that such an order would directly affect the religious beliefs of the parties and would violate the husband’s right to the free exercise of religion and as such, that the court could not attempt to compel a particular course of conduct before a religious tribunal. Notwithstanding any perceived “unfairness” of its decision to the wife, the court was of the view that this was a product of her own decision making in entering into the Ketubah, was a risk that she took and was not a line which the court should cross.

Given these conflicting trial court decisions, this issue was finally addressed by the Appellate Division in the case of Mayer-Kokler v. Kokler, 359 NJ Super 98 (App. Div. 2003). However, the resolution of this issue was less than definitive. In this case, the issue on appeal was whether the husband could be compelled to cooperate in giving the wife a Get. The parties had entered into a Ketubah; however, there was a dispute over the terms of same and whether it contained provisions concerning the securing of a Get. The wife requested that the court compel the husband to cooperate with efforts to secure a Get, but the trial court declined, stating that it did not believe it had the authority to do so, citing to Aflalo. The Appellate Division analyzed the Minkin, Burns and Aflalo decisions. After doing so, the Appellate Division concluded, however, that the issue turned on the terms of the particular Ketubah that the parties had executed, but noted the lack of a stipulated translation, the lack of proofs as to the effect of a Ketubah generally or this Ketubah in particular, and of what Mosaic law would require. Given this inadequate record, the Appellate Division then went on to hold:

“Even if a civil court may properly enforce such religious premarital agreements, notwithstanding First Amendment concerns, we are not competent to determine without an evidentiary basis whether this Ketubah effectively subjected defendant to comply with religious law and what that religious law demands here. Interpreting the effect of this Ketubah and then determining whether defendant’s signature of this document subjects him to Mosaic law, and further determining what Mosaic law commands on this point are not tasks which we should assume in the first instance and in any event are not tasks which we are properly suited in the absence of expert testimony and other evidence.” Id. at 104.

Therefore, while affirming the trial court’s order based upon the inadequate record, the Appellate Division nevertheless remanded “for the development of a more complete record as to the parties’s obligations under Mosaic law in the circumstances of this case, including the Ketubah and for a determination in light of such facts as to whether the court can compel the defendant to cooperate with plaintiff in obtaining a Get.” Id. at 105. Hence, it is clear that the Appellate Division rejected the reasoning of the court in Aflalo that a court is barred from entering such orders altogether, but rather, the issue turned more on the obligations under the parties’ marriage contract, i.e., Ketubah, so that the issue was more one of contract enforcement rather than an entanglement into religious doctrine. It is noteworthy that the Appellate Division seemed to cite with approval the court’s decision in Odatalla v. Odatalla, 355 NJ Super 305 (Ch. Div. 2002), in which the trial court enforced an Islamic Mahr Agreement contained in the parties’ marriage license requiring the husband to pay the wife a sum certain. Rejecting the husband’s First Amendment argument, the court opined that it could specifically enforce the terms of a Mahr Agreement provided it can be enforced based upon “neutral principles of law” and not on religious policy or theories and once applied, the agreement met those standards. The court was of the view that no religious or doctrinal issues were involved, and that it was not barred from enforcing same merely because it was entered into during an Islamic ceremony of marriage.

What can be taken from the state of the law if you are confronted with these sorts of issues in a divorce case? My initial conclusion is that a court would not compel a party to participate in any sort of religious divorce or annulment proceeding in the absence of some sort of contractual obligation entered into between the parties concerning same. If Jewish, did they have a Ketubah? If the parties are of the Islamic faith, did they have a Mahr Agreement? Be prepared, however, that religious experts may need to be involved that if there is a dispute as to its language, obligations or interpretation, as noted by the Appellate Division in Mayer-Kokler. Did the parties have an actual prenuptial agreement addressing these issues? Assuming that the court agrees that the prenuptial agreement itself should be enforced, such aspects of a prenuptial agreement may also be deemed enforceable as a matter of contract principles. Assuming that no pre-existing contract or agreement exists, these issues can certainly be negotiated as part of the overall divorce agreement. While you cannot force someone to agree to same, if such obligations become part of the divorce agreement itself, the court would certainly be likely to enforce same, again under contract principles rather than religious ones. As an attorney, you should address these issues with the client early on in the proceedings by asking if the religious aspects of divorce important to them. If so, they should be addressed as an aspect of the “civil” divorce process and not left to the potential for such reprehensible conduct noted at the beginning of this post.

New Jersey Divorce and Family Lawyer Blog

New Jersey Divorce and Family Lawyer Blog