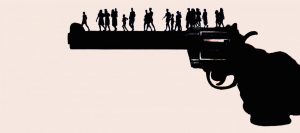

The Second Amendment of the Constitution of the United States of America, more commonly referred to as “the right to bear arms,” can  at times conflict with society’s ability to protect other citizens from those same citizens that have taken up their right bear arms. Nowhere is this more evident than in the tragic events that occurred in Dallas, TX this week where five police officers were killed by sniper fire coming from Micah Johnson who was later killed in a standoff with the police. The news reports are filled with stories of police being shot by citizens, citizens being shot by the police and fellow citizens being shot by their fellow citizens. Many people like to think that gun violence is limited to organized gangs; however, consider these statistics from the National Domestic Violence Hotline:

at times conflict with society’s ability to protect other citizens from those same citizens that have taken up their right bear arms. Nowhere is this more evident than in the tragic events that occurred in Dallas, TX this week where five police officers were killed by sniper fire coming from Micah Johnson who was later killed in a standoff with the police. The news reports are filled with stories of police being shot by citizens, citizens being shot by the police and fellow citizens being shot by their fellow citizens. Many people like to think that gun violence is limited to organized gangs; however, consider these statistics from the National Domestic Violence Hotline:

- Women in the U.S. are 11 times more likely to be murdered with guns than women in other high-income countries. [D. Hemenway and E.G. Richardson, “Homicide, Suicide, and Unintentional Firearm Fatality: Comparing the United States With Other High Income Countries, 2003,” 70 Journal of Trauma 238-42 (2011)].

- Female intimate partners are more likely to be murdered with a firearm than all other means combined. [When Men Murder Women: An Analysis of 2010 Homicide Data: Females Murdered by Males in Single Victim/Single Offender Incidents, Violence Policy Center. Washington, DC, January 17, 2013].

- The presence of a gun in domestic violence situations increases the risk of homicide for women by 500%. [J.C. Campbell, D.W. Webster, J. Koziol-McLain, et al., “Risk Factors For Femicide Within Physically Abusive Intimate Relationships: Results From a Multi-site Case Control Study,” 93 Amer. J. of Public Health 1089-1097 (2003).]

- In states that require a background check for every handgun sale, 38% fewer women are shot to death by intimate partners. [U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Supplementary Homicide Reports, 2010 (excludes New York due to incomplete data)].

On June 27, 2016, the Supreme Court of the United States held in the case of Voisine v. United States that: “Federal law prohibits any person convicted of a ‘misdemeanor crime of domestic violence’ from possessing a firearm. 18 U. S. C. §922(g)(9). That phrase is defined to include any misdemeanor committed against a domestic relation that necessarily involves the ‘use . . . of physical force.’ §921(a)(33)(A). The question presented here is whether misdemeanor assault convictions for reckless (as contrasted to knowing or intentional) conduct trigger the statutory firearms ban. We hold that they do.”

Three days later, on June 30, 2016, the Supreme Court of New Jersey voted unanimously in case of In re Application of State of New Jersey for Forfeiture of Personal Weapons & Firearms Identification Card Belonging to F.M.. to overturn the stayed decisions in the trial court and Appellate Division to allow a defendant accused of domestic violence the return of his guns and weapons. In New Jersey, the Legislature exercises of its authority to regulate firearms by requiring an individual seeking to purchase a handgun to first apply for an identification card and permit. N.J.S.A. 2C:58-3(a) and (b); 26 N.J.A.C. 13:54-2.2. N.J.S.A. 2C:58-3(c) provides that a “person of good character and good repute in the community in which he lives” must be issued an identification card and permit, unless that person is “subject to any of the disabilities set forth [therein].” See also N.J.A.C. 13:54-1.5. These disabilities apply to “any person where the issuance would not be in the interest of the public health, safety or welfare,” and “any person whose firearm is seized pursuant to the Prevention of Domestic Violence Act of 1991 . . . and whose firearm has not been returned[.]” N.J.S.A. 2C:58-3(c)(5) and (8); see also N.J.A.C. 13:54-1.5(a)(5). “[T]he statutory design is to prevent firearms from coming into the hands of persons likely to pose a danger to the public.” State v. Cunningham, 186 N.J. Super. 502, 511 (App. Div. 1982). N.J.S.A. 2C:58-3(f) provides that “[a]ny firearms purchaser identification card may be revoked… upon a finding that the holder thereof no longer qualifies for the issuance of such permit.” The burden is on the State to prove, “by a preponderance of the evidence, that forfeiture is legally warranted.” State v. Cordoma, 372 N.J. Super. 524, 533 (App. Div. 2004).

The incidents of domestic violence alleged in the New Jersey case involved both physical and verbal abuse by F.M. upon his wife. After one altercation, a temporary restraining order (TRO) was entered and F.M.’s weapons were seized. The trial court later dismissed the TRO but opposed the return of weapons to F.M., who was also a police officer. The State presented two experts. Dr. Matthew Guller, a licensed psychologist and board-certified police psychologist and who performed a Fitness for Duty (FFD) evaluation on F.M. following the March 14 incident, concluded that F.M. was not fit for full duty and recommended that he be disarmed because he was a “danger[] to himself or others.” Dr. Lewis Schlosser, also a licensed psychologist, concluded that F.M. was “psychologically impaired for the role of a municipal police officer and, therefore, not fit for duty.” Dr. Schlosser acknowledged that he had not performed an evaluation on whether F.M. should possess a personal firearm, “but in light of the events in the record, [he] would have concern for [G.M.] should [F.M.] have a private firearm.” The Appellate Division and Trial Court agreed that aforementioned psychologist testimony, the testimony of the police officer who responded to the domestic violence call, and the victim’s testimony did not did not overcome the infringement on F.M’s right to bear arms, agreeing that the weapon should be returned to F.M.

The New Jersey Supreme Court disagreed, holding the Family Part applied an incorrect legal standard and that the trial court’s conclusions were not supported by substantial, credible evidence in the record. The Supreme Court Justices found that the record established that the return of F.M.’s personal weapon and identification card was inconsistent with N.J.S.A. 2C:58-3(c)(5) and determined that F.M.’s weapon and identification card were forfeited.

Clearly, the issue of gun control versus Second Amendment rights is a deeply contested issue in our country now given the times that we are in, and both the legislative bodies and the courts continue to struggle with balancing the public’s protection with citizens’ constitutional rights. These issues play out even in the family courts.

New Jersey Divorce and Family Lawyer Blog

New Jersey Divorce and Family Lawyer Blog